Walking through the Tibetan quarter of Lhasa, it is easy to imagine it is still the Forbidden City that lay hidden on the roof of the world for so long.

The architecture has changed little in hundreds of years and the narrow Streets teem with pilgrims and monks.

The air is thick with spirituality - made all the more poignant by your own altitude-induced light headedness and the heavy tang of juniper incense. In the old town is the Jokhang Temple, the holiest site in Tibetan Buddhism.

It sits at the centre of three pilgrimage circuits and the faith walk around the temple daily - always clockwise. The outer circuit runs around the town’s perimeter, whereas the middle one - the Barkhor - circles the Jokhang.

Mixed crowd

The pilgrimage draws believers from all over Tibet: scarlet-robed monks, Golok nomads in sheepskin coats, Khambas whose hair is beaded with threads, wizened old women. Most people are counting off prayers on swings of beads.

The most devout gravitate towards Barkhor. Clad in leather aprons and wearing wooden paddles on their hands for protection, they throw themselves onto the ground, the paddles clattering on the paving flags. They then bring their hands together, mumble a prayer, get back on their feet, pray again and repeat the diving motion - inching forward each time. I’m humbled by their dedication as I make my way towards a café for a lunch of the ubiquitous momo - dumplings stuffed with potato and yak meat.

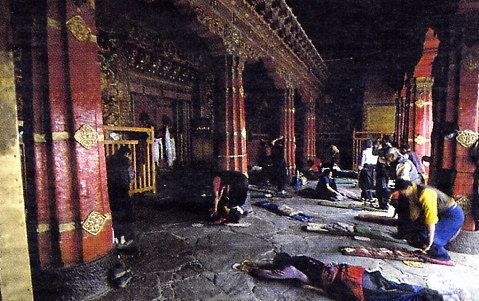

At the front of the lokhang, scores of pilgrims prostrate and pray repeatedly. Perhaps when life is as hard as it is for the avenge Tibetan, any sacrifice has to be extreme.

Within the temple’s great walls is the final circuit, around the exterior of the main prayer hall. It is lined by a series of copper prayer wheels that the pilgrims spin as they walk, sending prayers up to heaven. Inside the dark, mysterious interior of the hall, the air hangs with the odour of yak-butter lamps and the drone of the monks’ chants. Pilgrims file past a golden statue of Buddha.

China town

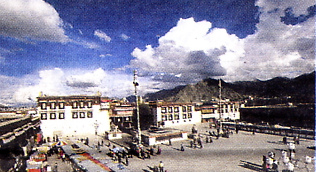

Lhasa’s most iconic structure the Potala Palace (below) which is swallowed up by the gaudy, ferro-concrete sprawl the new Chinese town.

Exploring the palace’s ornate rooms reminds you shat it should be the home of the Dalai Lama. But, following the Chinese invasion and the flight of the spiritual leader of Tibet, it has become a museum.

Monks occupy each room, although rumour has it they are secret police in disguise.

So many Han Chinese have immigrated here that today’s Tibetans are a minority in their own country.

The world has ignored their plight and they have lost any hope of self-rule. Even the Dalai Lama has said he never expects his country to be free.

Yet by visiting - and patronising only Tibetan-owned businesses - you can go some way towards demonstrating your support.

A 15day tour includes Lhassa, Kathmandu and Everest Base Camp. Prices start at, £670, plus a £160 local fee’ to boost local business.

Gulf Air flights to Kathmandu with Intrepid are £463. Tel. 0870 220 6980, wviw.intrepideravel.com

London readers can visit their new store at 76 Upper street N1.

BARE ESSENTIALS

At 3,750m above the Lhasa River, Tibet’s capital Lhasa is one of the highest cities in the world. May, June, July and August are the best times to go.

Language: Tibetan, Mandarin and Cantonese Currency: £1 = 15.5 China Yuan Renminbi

Culture corner

What to do - and what not to do - In ‘Tibet

• While sticking your thumbs up with a huge grin may be an almost universal sign for ‘well done’, in Tibet you’re more likely to get cash thrown at you. It means you are begging

• Here in the West, sticking your tongue out at someone is rude but in Tibet it is considered polite and respectful

•Taking part in any Tibetan independence demonstrations will see you deported- even photographing or videoing such events will have the same effect.